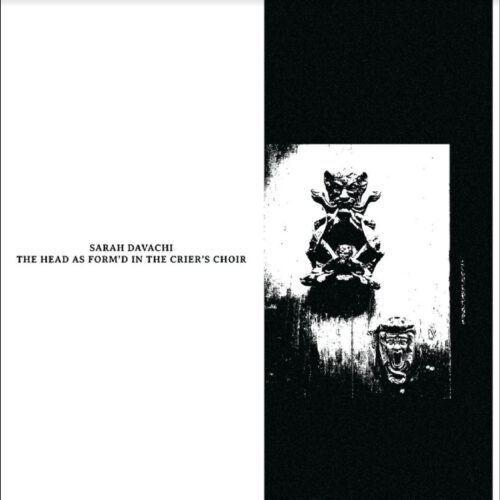

The Head as Form’d in the Crier’s Choir

Label: Late Music

Genre: Highlights, Electronic, Experimental

$46.99

Availability: In stock

Audiopile Review: Canadian minimalist composer Sarah Davachi has an extraordinary ear and an uncanny ability to turn simple tones into seething, writhing worlds of sound. The title of her latest work, ‘The Head as Form’d in the Crier’s Choir’, may sound hauntingly medieval, but it’s really an ancient Greek reference. And this album could just as easily be the music of far-future ascetic monks in some obscure corner of the galaxy, chanting down a neo-feudal galactic Babylon. So, is this album Beowulf, the Odyssey, or Dune? None and all the above. While a Sarah Davachi composition is always evocative, you’d be hard-pressed to locate her intent via known coordinates. And ‘The Head as Form’d…’ finds her in a space exclusively her own. But it’s not just a matter of time and space, like the best minimal music, the pieces collected here seem to alter the fundamental basis of matter itself. There she is, transforming single, extended notes into complex sound-worlds, making acoustic instruments sound futuristic and high-end synthesizers sound ancient. And this is perhaps her most accomplished melding of acoustic and electronic elements to date. We should also mention that it really is very haunting. There’s an arrestingly ominous sense of melancholy throughout this album, with a straightforward beauty reflecting through its sonic hall of mirrors.

The compositions on this album, written between 2022 and 2024, form a conceptual suite and an observance of the mental dances that we construct to understand acts of passage; the ways that we commune, memorialize, and carry symbols back into the world beyond representation.

To this end, The Head as Form’d in the Crier’s Choir engages two references to the ancient Greek myth of Orpheus: Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus, a collection of poems from 1922, and Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo, an early baroque opera from 1607.

The Head as Form’d in the Crier’s Choir follows on from the last two albums, which were attempts to begin bridging the gap between the fixed electroacoustic pieces that emerge in Davachi’s home studio and her slow-paced, somewhat open-form chamber writing, in which each performance presents a new structure and each iteration offers the path to a new composition and deeper meaning.